In the past the dowry was a custom intended to be a material protection for each new couple. It was a kind of insurance giving them the means to start a new life together and to settle comfortably. This donation made by the father of the bride originated in Roman law, the “propter nuptias.” In case of a rupture of the union, the dowry was to be kept by the wife. This dowry consisted of a variety of goods and was determined by the wealth of her family. It was comprised of money, acreage, cattle and other farm animals, articles of furniture, and “le trousseau” of the bride with her fabrics, lace, bedding , table linen….

From the youngest age the bride-to-be prepared and often herself created her trousseau without yet knowing to whom she would one day be wed. The word “trousseau” comes from the ancient French word “trouser”, to wrap as in a package. The trousseau was, in effect, the package of linens that this young bride brought with her upon leaving her family home. She embroidered her initials on her bedclothes, and on her finest linens she always left a space for those of her future husband as she would not yet have known what initials these would be. As such, antique linen which only bears one initial is more often than not the testimony of a union which never came to pass.

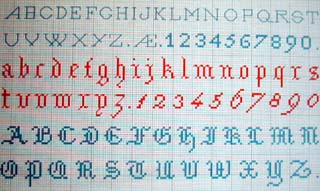

The trousseau was often comprised of numerous sheets (twelve was common for a wealthy family), numerous dish towels, hand towels, napkins and tablecloths patiently and meticulously embroidered. To mark these linens with one’s initials was an inherent part of every young girl’s education. And in fact the sampler, or “abcdaire,” was the pride of each little girl who arrived in the adult world. On a swath of cloth, she embroidered in needlepoint the letters of the alphabet as well as the numbers from zero to nine. The initialled letters of the “marquoir,” or the family stamp, were always “blood red,” a symbolic reference of the young girl’s destiny as a woman. Why red? Because red was also a strong and durable dye, resistant to multiple launderings and one that could be easily seen. Before the era of chemistry the colorant widely used was “common madder,” or “rubia tinctorum.” Common madder belongs to the vast plant world family of rubiaceae, quite a remarkable family in that it also includes the plants that produce coffee beans and quinine. A perennial plant, common madder has evergreen leaves, tiny yellow/white flowers and reddish black pea-sized berries. However, it’s in the roots that the pigment is found that is the source of the dye known today as alizarin.

Unlike the refined art of embroidered linens, which was realised in white on white, the stitching of these red letters had a purely utilitarian role and was executed in a simple cross-hatched needlepoint. The letters served to organize sheets that were made in pairs of a top and bottom sheet, and next to these letters, small numbers were often also marked. These numbers were a kind of rank that allowed the sheets to be alternated equally between washings but they also served as a kind of accounting as the family linens had a very great value. And very often a young girl marked her linens with her own initials to distinguish these from those of her mother and grandmother. Sometimes too she inscribed the name of her town or village.

In more simple households, to create one’s own trousseau was a big contribution to the household chores and maintenance. The dowry represented a linen supply for a lifetime and often was inherited by subsequent generations. The linens that required special or individual treatment were only laundered twice per year, in the spring and in the autumn (thus the need for an abundance of linens!). This grand laundering ceremony lasted for several days in public laundry houses or by the banks of the local river. The clean laundry was then lain in fields and dried by the strong seasonal winds.

The armoire where linens were traditionally stored appeared toward the end of the 14th century, and the custom of making a gift of a marriage armoire, sculpted with symbols of abundance and fecundity, spread as far as the 18th century. The trousseau of the 19th century represented an important stage in social life, not only of marriage but also of birth (the trousseau of the newborn child), of the departure for boarding school (where the linens were marked in red either with a number or with the initials of the child), as well as of the entry into the convent.

The creation of the trousseau has always been in the hands of women. This comprised weaving, sewing, embroidery… and these practices weren’t exclusive to the common classes. The aristocracy, all the way up to the royal families, practiced these arts. From the most tender age, each young girl prepared her marriage trousseau which would accompany her up to her death, especially as she sometimes also embroidered her mortuary sheet. Very, very often at the price of great suffering and hours of incalculable patience, a long apprenticeship began by the mastery of the spinning wheel, the bobbin and the needle. When she had become sufficiently adept, she began to sew and embroider first fabric, and then later the linens.

In the 19th century, fancier hand towels replaced the bath cloth, a simple length of toile which until then seemed to be sufficient. At this time too, the number of pieces of the trousseau, the quality of the fabric of each element and its ornaments, initials, ribbons, pleats, cutwork, lace or embroidery, of which certain were more appreciated than the family jewels, constituted a supplemental means for families to affirm their social standing. The family linens, of a great richness, were represented there in sometimes dizzying quantities, while the poorest social classes strived with great difficulty to provide their daughters with even one unique sheet.

It was in the 18th century that the expression “marriage basket” first appeared. It was applied to the presents that were offered, in woven baskets, to the young girl by her financé. By extension the marriage basket came to mean the entire ensemble of presents that he made to her during the engagement period, which then evolved later and to the present day to mean the totality of gifts offered to the young bride and groom. In the 19th century the young girl would find there jewellery, offered to her by her mother-in-law, lengths of fabric, furs and multiple trinkets and ribbons, all of which would come to embellish her “toilettes.” As a general rule, the family linens were initialled in the two family names of the spouses, while personal linens carried the initials of their first and last names. For babies, the word “bébé” would be embroidered and for the older children their entire first name. When it was a question of everyday linens like dish towels, the family initials were marked in simple, red needle-point cross stitches. On the other hand, the fine quality bed and table linens were ornamented with embroidered white on white initials that were elaborately decorated and very finely worked. In families of nobility, a crown often appeared in the embroidered motif.

Up until the 20th century the clothing of the bride, her dresses, coats, capes, dressing gowns…. all were part of the trousseau. However, the world of popular fashion, which tempted women to renew more and more often their wardrobe, resulted in the disappearance of articles of clothing from the trousseau. By the beginning of the 20th century, the bride’s trousseau had evolved such that it only included her family and personal linens: the sheets, pillow shams, tablecloths, napkins, dish towels and hand towels, as well as her bed clothes and underclothes: corsets, nightgowns, slips, bloomers, stockings, collars and sleeves.